Anecdotes of CICS Development

This article was made in response for a “call for history” in 2019 in anticipation of the 50th anniverary of IBM’s program product CICS. The call asked particularly for memories of the CICS Restructure project.

Anecdotes of CICS Development

I joined the CICS Development team as a freelance programmer in 1975 / 1976 and joined IBM as a permanent member of staff in 1976. My time in CICS Development formed a vey important part of my life. I think about it a lot and am glad to have the opportunity to recall some memories.

Firstly:

Z and CICS Restructure

CICS Restructure was a landmark event in the history of CICS, following the 1977 Exec/ Command-level Application Programming Interface in COBOL etc.which made CICS available to thousands of programmers around the world. These events definitively put Hursley’s stamp on the “inherited” software.

It was decided in 1983 to invest resources in a major restructuring of the internals of CICS to clarify internal interfaces and to provide the basis for future development of CICS. And to help the Restructure team make sense of the structure they wanted, and to ensure the new modules fitted in with the old modules untouched by Restructure, they used the Z notation to specify, in a precise mathematical notation, the behaviour of CICS’s restructured parts. The very substantial benefits of this decision are summarised in this publication from 1991:

I.S.C.Houston and S.King. CICS project report: Experiences and results from the use of Z in IBM. In S. Prehn and W. J. Toetenel, editors, VDM’91: Formal Software Development Methods, volume 551 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 588-596. Springer-Verlag, 1991

But Restructure was not the only thing going on at the time. I was not part of the Restructure team itself, but I participated in many of the specification and code inspections as did other programmers from teams across CICS Development. In this way, expertise in how the restructured modules should work was combined with wider expertise on how the specifications should be implemented.

You can see an example of this cross-pollination between concurrent CICS product offerings when you consider that CICS Restructure was developed for CICS/ESA V3.1 for the MVS operating system platform, being developed alongside CICS/VS running with a tiny “working set” memory footprint - merely 10’s of Kilobytes! - destined for the IBM DOS OS platform (?DOS-ENTRY (program number 5736-XX6) for DOS/360 machines).

Both CICS/ESA Restructure and CICS/VS required a Storage Control Program (DFHSCP), and the performance constraints on the CCS/VS version of DFHSCP were paramount from the start. The more complex functionality - multiple storage pools, for example - of the restructured CICS/ESA DFHSCP was specified formally in Z but the performance characteristics were not initially a prominent part of the specification. In code inspections David Page and Iain Houston provided their CICS/VS performance-tested DFHSCP as proof of concept for some aspects the eventual performant CICS/ESA DFHSCP, namely the avoidance of unnecessary page faults.

The previous example brings out a significant point for those interested in the software development process we were deploying at that time. For CICS Restructure, the “waterfall” from the formal, mathematical, Z specification to code - “waterfall” being the most appropriate process here - was essentially an informal step. Peter Lupton worked with Carroll Morgan of the Programming Research Group on program verification methods; in the event the Restructure team employed one or more levels of specification-to-design “refinement” in Dijkstra’s language of guarded commands, but in most cases there was no formal relationship between the documents produced at different levels of abstraction, and so very little proof work was done to establish that the code was a correct implementation of the Z specification, although the preconditions of operations were recorded. Nevertheless, even though an ideal formal program refinement process was not possible, the benefits of being “as formal as practically possible” resulted in tremendous savings in testing costs and maintenance costs once the product had become available to customers at the end of June 1990. This was due to everybody involved knowing precisely and unambiguously how each restructured module was supposed to behave.

Queen’s Award for Technological Achievement

In collaboration with the Oxford University Computing Laboratory, under the leadership of Tony Hoare, this work with Z won, jointly, the Queen’s Award for Technological Achievement.

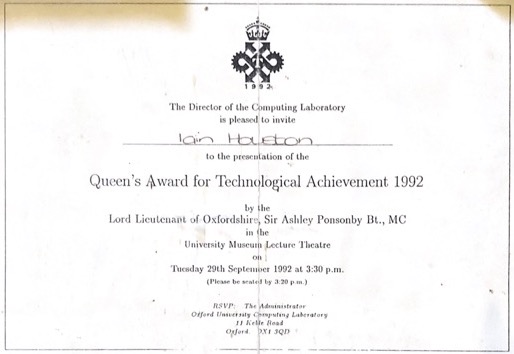

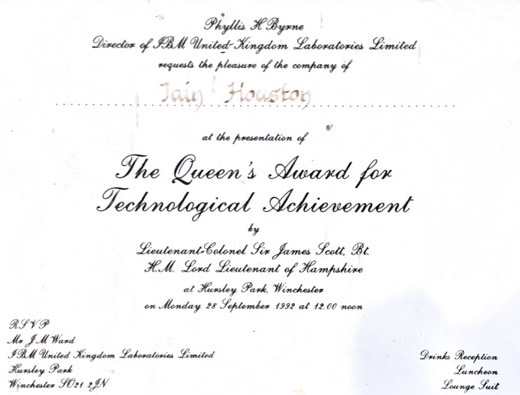

Queens Award Commemoration Events

Queens Award (IBM)

Queens Award (Oxford University Computing Lab)